Glaucoma Surgery

All glaucoma surgery procedures (whether laser or non-laser) are designed to accomplish one of two basic results: decrease the production of intraocular fluid (aqueous humor) or increase the outflow (drainage) of this same fluid. Occasionally, a procedure will accomplish both.

Currently the goal of glaucoma surgery and other glaucoma treatment is to reduce or stabilize intraocular pressure (IOP). When this goal is accomplished, damage to ocular structures — especially the optic nerve — may be prevented.

No matter the treatment, early diagnosis is the best way to prevent vision loss from glaucoma. See your Ophthalmologist routinely for a complete eye examination, including a check of your IOP, visual field check up and optic nerve assessment. People at high risk for glaucoma due to elevated intraocular pressure, family history, ethnic background, age or optic nerve appearance may need more frequent visits to the eye doctor.

When Is Glaucoma Surgery Needed?

Depending on the type of glaucoma you have, different treatment options may be considered. Non-surgical options include the use of topical eye medications (glaucoma eye drops) or oral medications (pills).

Most cases of glaucoma can be controlled with one or more drugs. But some people may require surgery to reduce their IOP further to a safe level by improving the outflow or drainage of fluids. Occasionally, surgery can eliminate the need for glaucoma eye drops. However, you may need to continue with eye drops even after having glaucoma surgery.

Routinely performed glaucoma surgery is “trabeculectomy” which creates an artificial drainage area. This method is used in cases of advanced glaucoma where optic nerve damage has occurred and the IOP continues to soar. Other options are glaucoma shunts (a device that a surgeon implants in your eye to improve fluid drainage) and non penetrating glaucoma surgeries.

Trabeculectomy

A trabeculectomy is the most common type of surgery performed to control IOP. Essentially the surgeon will create a trap door into the anterior chamber to allow aqueous to flow out, completely bypassing the trabecular meshwork. Before the operation the patient should discuss all the potential risk factors with the ophthalmologist that may cause complications or even failure of the surgery.

There are several new surgeries for glaucoma, despite that trabeculectomy remains most commonly performed glaucoma surgery for lowering IOP, especially in eyes which have not previously been operated on.

The operation is usually carried out under local anaesthetic, with injections. Usually surgery lasts up to 30 -35 minutes.

Depending upon the risk factors for surgical failure, which will have been assessed by the ophthalmologist in advance, some patients may be prescribed steroid eye drops and/or antibiotic eye drops shortly before surgery. However this is not necessary in the majority of cases.

The Trabeculectomy Procedure

A large flap is cut into the conjunctiva which is then lifted up to expose the sclera. Any bleeding is stopped by cautery.

A second flap into the sclera is cut which is only about halfway through the full thickness of the sclera. Then a scleral ostium is cut out of the remaining sclera, forming an aperture (sclerostomy) through the sclera into the anterior chamber to allow the outflow of aqueous.

An iridectomy is also performed, removing a section of iris below the sclerostomy, to prevent it from moving upward towards the aperture and blocking aqueous from flowing through. At this stage aqueous will begin flowing out through the gap created in the sclera.

The flap of sclera is then sutured down over the sclerostomy at a desired tension to control the rate of outflow. After the operation the surgeon can release stitches as required to regulate the rate of aqueous outflow and therefore the IOP.

Finally the conjunctiva is drawn back over the sclera ‘trapdoor’ and sutured down tightly to restrict any leakage. This creates a layer of tissue over the wound site called a bleb. The bleb acts as a natural filter allowing outflow from the anterior chamber but at the same time controlling the rate of flow.

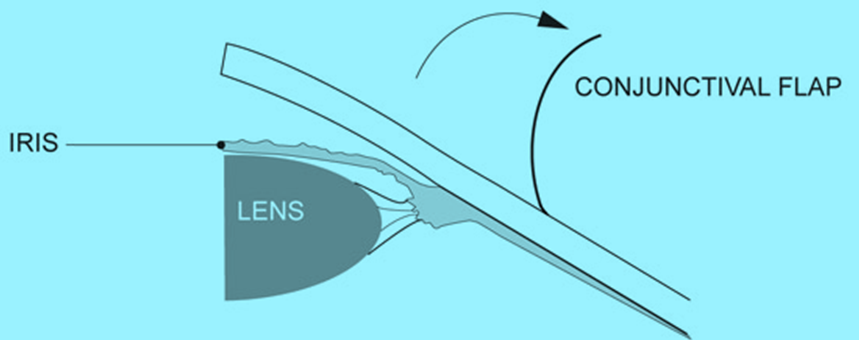

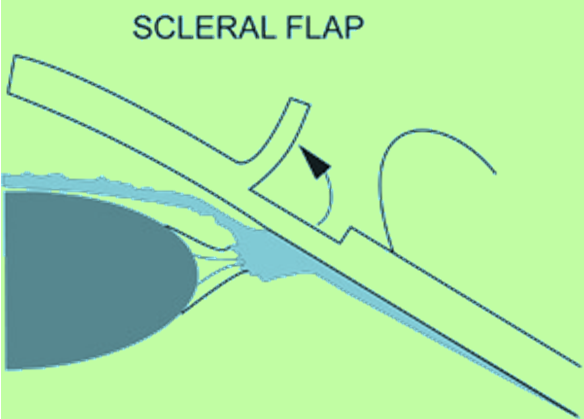

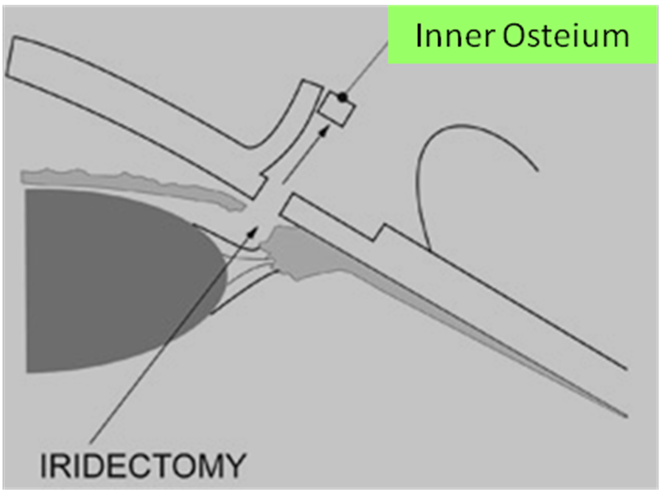

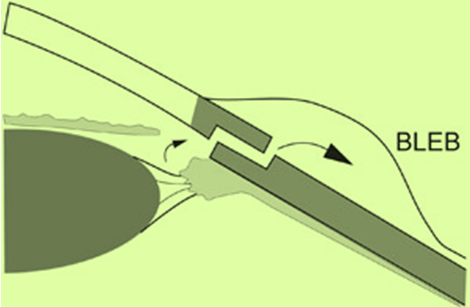

The following series of illustrations shows the sequence of the trabeculetomy surgical procedure.

1. Firstly a conjunctival flap is cut and lifted up.

2. Secondly a scleral flap (approximate size 4X 4 mm rectangular flap) is cut and lifted up.

3. Next, a sclerlis removed from inner sclera flap (approximate 2 X 2 mm) is removed from the remaining thickness of the sclera, so that there is now an open channel into the anterior chamber. An iridectomy (removal of iris just below where we have created ostium) is also performed.

4. And finally the scleral and conjunctival flaps are sutured back down to form a drainage area known as a bleb.

A key factor which causes this surgery to fail is the natural scarring response in the eye. To combat this wound-healing effect, ophthalmologists will deploy one of a number of medications during the time of surgery which are specifically designed for the inhibition of scarring. These agents include mitomycin-C or 5-flurouracil.

Immediately post-operatively the patient will be given steroid eye drops, antibiotic eye drops and eye drops that dilate their pupils. The patient will usually receive a check up the next day after surgery, potentially every day for the first few days and then again regularly, maybe even every week depending upon the patient and the surgeon, for the first six to eight weeks. These are the most critical weeks because this is when the rate of drainage needs to be managed very closely to prevent an IOP which is either too high or too low.

During follow-up visits the surgeon will check your IOP and may often adjust the flap of the ‘trapdoor’ by either loosening or tightening the sutures as applicable. At the same time the surgeon may also use a needle to clear away any obstructions under the bleb and inject more anti-scarring agents. These procedures are not painful and most patients will feel only mild discomfort.

The ophthalmologist may also massage the eye and/or ask the patient to do so in order to encourage outflow through the new channel created by the trabeculectomy.

Unlike many other surgical procedures the post-operative phase of managing the trabeculectomy is just as important as the surgery itself.

Even after a successful surgery with no complications there are a number of variables regarding the surgery site which need to be carefully managed in order to ensure that the trabeculectomy is a success.

The ophthalmologist will be dealing with a wound site which may be inflamed or blocked by debris, and will have to use a combination of mechanical intervention and different types of drugs as tools to regulate the following factors:

– Excessive aqueous flow;

– Insufficient aqueous flow;

– Inflammation;

– Bleb leakage;

– Shallow or inflamed anterior chamber;

– Hyphema;

– Synechiae (PAS) formation

The filtration site is a dynamic work in progress which needs to be carefully managed by the ophthalmologist as it stabilises in the first few days and weeks.

usually after two to three weeks, the ophthalmologist may also release the sutures on the scleral flap. Depending upon the type of suture used during the surgery, releasable sutures can just be removed at the slit lamp. Fixed sutures need to be cut using a process known as laser suturelysis. This is the use of a laser to cut the sutures in the scleral flap. Releasing or cutting sutures, usually one at a time, is done to increase aqueous outflow to lower IOP.

Generally your surgeon will prefer to achieve a slightly higher post-operative IOP than is desirable, and then lower it, rather than end up with an IOP that is too low. An IOP which is too low is more problematic to deal with, as there is therefore a high risk of hypotony which can cause very serious post-operative complications.

Patients should be aware that there may be temporary deterioration in visual acuity in the first few weeks after surgery which improves to the baseline vision what patient had before surgery.

Complications Related To Trabeculectomy Surgery

Complications specific to trabeculectomies generally revolve around issues connected to hypotony, such as overfiltration or bleb/wound leakage and the anterior chamber becoming flat. Other common post-operative complications can include:

– Aqueous Misdirection; is where aqueous flows rearwards into the vitreous cavity. There is no provision for outflow in the vitreous cavity, so this results in an immediate increase in IOP and the lens and iris being pushed forward, closing the angle completely.

Eyedrops such as cycloplegics to freeze the iris and carbonic anhydrase inhibitors to suppress aqueous production are required immediately, followed by surgery to allow the aqueous to flow back into the anterior chamber. Miotics should be avoided and discontinued if already in use.

– Blebitis; and bleb related endopthalmitis, which is described at the beginning of this chapter;

– Corneal complications;

– Cyclodialysis cleft;

– Early postoperative increase in IOP for a number of reasons relating to blockage of outflow;

– Pupil block; and

– Suprachoroidal Haemorrhage and Choroidal Detachment; which are more common in cases of hypotony. Suprachoroidal Haemorrhage is extremely painful for the patient. It is potentially the most devastating complication because in cases of severe bleeding there is a poor visual prognosis for the patient, even after the problem is repaired. Fortunately it is rare.

Due to the long history of trabeculectomy surgery, ophthalmologists are well informed and practised in the various indicative signs of each of these complications and the medical and surgical management required to control them.

It is also expected (rather than regarded as a complication) that trabeculectomy surgery stimulates cataract formation. Approximately 50% of patients who have trabeculectomy surgery will develop cataracts as a result and may require lens extraction surgery, which often has a negative knock-on effect on the trabeculectomy itself.

As mentioned previously, if possible ophthalmologists will try and plan the surgeries so that cataracts are removed before, or at the same time as trabeculectomy surgery.

High Risk group who can develop Complications

The primary risk factors are:

Patient who had any previous ocular surgery, especially vitreoretinal surgery or previous failed glaucoma filtration surgery;

– History of uveitis (inflammation of eye)

– High degree of near-sightedness of farsightedness, or any other condition resulting in unusually ‘short’ or ‘long’ eyes;

– Eye Allergies;

– Young Age, older patients tend to do better, those under 30 especially tend to do worse;

– Diabetes;

– Type of glaucoma, e.g. secondary neovascular, uveitic or trauma induced glaucoma;

– Potential infections, e.g. blepharitis;

– Ocular surface disease;

These risk factors do not always mean that the patient is unsuitable for a trabeculectomy, but the doctor may have to stop the patient taking some medications well before surgery, prescribe other medications and also ensure that any other conditions are well controlled before the procedure. Some of these patients (like secondary neovascular, uveitic or trauma induced glaucoma patients) may require glaucoma drainage device implantation.

Many of the risk factors above, such as youth, race, inflammatory disorders, type of glaucoma, the preservatives in many eyedrops and any previous surgeries are believed to ‘prime’ or ‘activate’ the conjunctiva, leading to a very aggressive inflammatory response to filtering surgery.

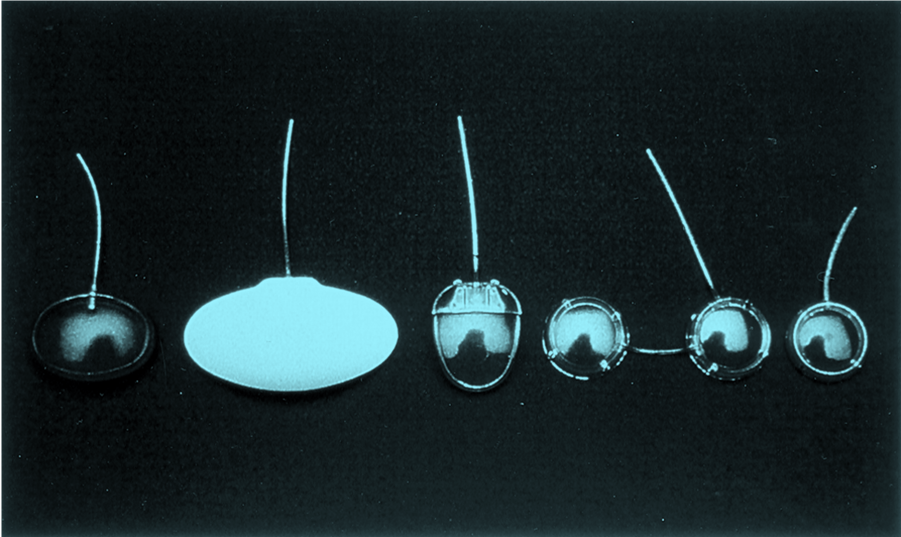

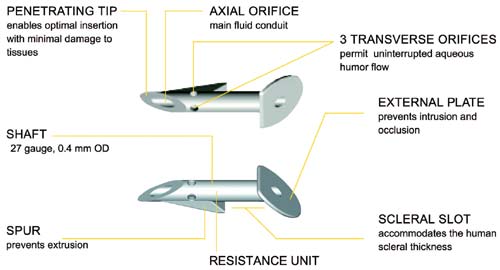

Shunts and Implants for Glaucoma

Glaucoma shunts and stents are small devices that are surgically inserted into the eye during a trabeculectomy to increase outflow of intraocular fluid and reduce high eye pressure.

The devices, usually made of materials such as silicone, polypropylene or biocompatible metals, create an alternative passageway for the aqueous to escape from the eye, bypassing the eye’s damaged or clogged filtration drainage canals.

The term “glaucoma implants” sometimes is used to describe shunts and stents, but also describes tiny devices implanted in the eye that are designed to provide a sustained release of glaucoma medicine to reduce eye pressure.

Complications of these implants can include creating a pressure that is too low for the eye to function (hypotony). Implants also can be positioned too close to the front of the eye’s surface, causing corneal erosion. They also can cause erosions in the eye tissues where they have been placed. Despite these risks, shunts and implants for glaucoma typically are safe and effective and can decrease or eliminate the need for daily glaucoma medications.

![]()

NEWER GLAUCOMA IMPLANTS:

Nonpenetrating Glaucoma Surgery (NPGS)

Various innovative surgical techniques alter the eye’s drainage channels, improving the flow of fluids with only minimal penetration into the eye. These surgical methods involve superficial incisions that do not penetrate the eye as deeply as, for example, a trabeculectomy. Proponents say fewer complications are likely to result from these less invasive procedures.

A deep sclerectomy involves a minimally invasive incision into the white of the eye (sclera), a portion of which is removed to create a drainage space for relief of eye pressure.

Surgical Steps:

Creating an outer scleral flap and removing the inner scleral flap

A new surgical method known as viscocanalostomy creates an opening for insertion of a highly pliable, gel-like material known as viscoelastic, which helps provide enough space for adequate drainage and eye pressure relief.

The success of these surgeries is not as high as trabeculectomy and is contraindicated for angle closure glaucoma which is common is India.

Glaucoma Surgeries for pediatric glaucoma: Trabeculotomy and Goniotomy

A goniotomy typically is used for infants and small children, when a special lens is needed for viewing the inner eye structures to create openings in the trabecular meshwork to allow drainage of fluids.

A trabeculotomy is the same as a trabeculectomy, except that incisions are made without removal of tissue. This surgery is similar to goniotomy; opening the Scleman’s canal from outside.